Putting Infrastructure

Back to Work

Putting Infrastructure

Back to Work

MYSTIC WATERWORKS PUMP STATION, SOMERVILLE MASSACHUSETTS 2017

Robert Campbell, architectural critic for The Boston Globe, raised the following relevant questions when our Chestnut Hill Waterworks project opened in 2008.

“Why was the architecture so lavish? Should we worry, perhaps, that corruption was at work? Did officials receive kickbacks in return for spending too much public money on the buildings and their builders? This was, after all, the age of notorious political bosses in American cities, including Boston.

Maybe that happened, maybe not. When you look at the result, it’s hard to feel puritanical about the process. Sometimes it’s better to spend too much than to spend, as we usually do today, far too little.”

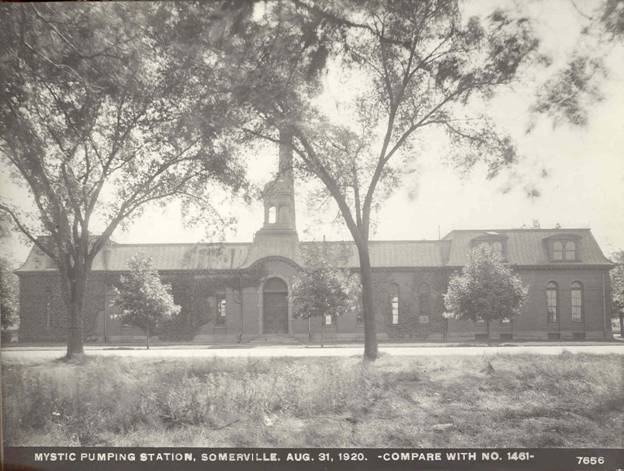

Boston benefits from many examples of high-quality infrastructure and public realm projects completed a century ago that are either still in use or robust enough to be repurposed with a new life. The Mystic Waterworks Pumping Station in Somerville was such a candidate for re-use due to its in-town location and proximity to the Somerville Housing Authority’s Capen Court Senior Housing complex.

BACKGROUND

In the early development of Boston, the need for clean water was solved by continually moving west. Sources of clean water were found that could be pumped into the city until the Quabbin Reservoir was constructed in central Massachusetts that still services us today. According to an article by Allston-Brighton historian, Dr. William P. Marchione, the population growth that drove the search for additional water resources continued as outlined below:

“In the 1870 to 1900 period Boston’s population more than doubled, rising from 250,000 to 560,000 (some of the increase occasioned by the annexation of surrounding cities and towns). The city’s water supply system thus required further expansion. A number of stopgap measures were resorted to in the 1870s to increase the supply, including the construction of six small reservoirs on the Sudbury River and its tributaries, which provided another 13 million gallons for the city. In addition, with the annexation of the City of Charlestown in 1874, Boston acquired the water rights to Mystic Lake, which added 7 million more gallons to its overall water supply.”

–The Allston-Brighton Tab or Boston Tab newspaper articles, July 1998 to late 2001

The building continued to pump water for the city until 1912 when it was decommissioned and the pumps and engines were sold as scrap metal. During the First World War, the interior was divided up into offices for research, and also incorporated new mezzanine and attic levels. Another subsequent renovation in 1921 further moved the building from its original use and its original layout of a singular large open space.

PROPOSING A NEW PURPOSE

“The redevelopment of Mystic Water Works presents an extraordinary opportunity to provide 25 units of affordable housing for very low-income elders while restoring a highly visible dilapidated historic building to its former beauty and also completing the Capen Court housing project,” wrote the Somerville Housing Authority in its application for CPA funds for the project. This sums up the logic behind the proposed redevelopment and suggests a process for tackling other infrastructure assets that are no longer in use, but well-located.

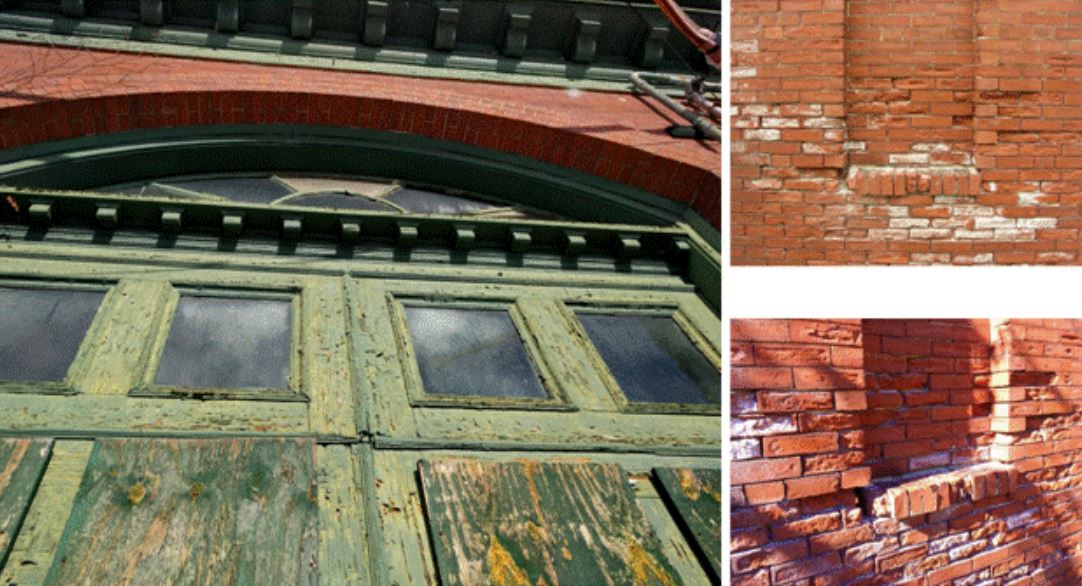

Our involvement began in 2011 when we were awarded the commission to convert this historic building into senior housing, combining two areas of our expertise — senior living facilities and adaptive re-use. The building had been neglected over the years and we found it in rough shape. The exterior brick was deteriorating in many areas and needed repair and re-pointing, the original wood windows and doors were falling apart, a new roof was in order and many interior additions needed to be demolished and removed delicately without damaging the main shell of the building.

Windows are often a challenge in historic buildings and it was no different in this case. Aesthetics, early construction methods, and glass type all clash with desires for increased weather tightness, energy efficiency, current fabrication methods, and cost. As with most affordable housing projects, the funding sources are many and often come with requirements like those associated with historic tax credits. Working with MHA as our historic advisor, we needed to comply with The Secretary of Interior’s Standards for the treatment of historic structures to maintain the viability of these tax credits to help finance the project. Key to the financial viability of the project was to fit two levels of units into the high bay space of the pumping station and this had implications for the meeting rail of the existing windows, which is where we determined the floor should interface with the windows. This was suggested by how the mezzanine floor had been inserted early in the 20th century just below the arch top sash. Balancing the window profile and site lines with floor to floor acoustic requirements, we proposed our solution to the reviewers from the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC) and the National Park Service (NPS) and were rejected. Benefitting from MHA’s experience with the reviewing agencies, we immediately filed an appeal, re-designed the floor to mullion connection, and flew down to Washington, D.C. to make our case. It should be noted that you only get one appeal. If rejected, you cannot take advantage of the historical tax credits, which would have put the financing of this project in jeopardy. The team pleaded our case and as luck would have it, our reviewer was familiar with the building since his daughter attended Tufts University and he had driven past the dilapidated structure countless times. He understood the importance to re-use and rehabilitate the building as well as the need for affordable senior housing. He approved the redesigned window details so that the project could move forward.

Ed, I remember when this project started but did not realize that it finally got completed, and completed so nicely. I enjoyed reading about the history of the water pumping system of the past and the successful process of convincing the historical review agencies to ultimately approval the project. Congrats to the project team.

What a beautiful example of adaptive reuse. Well done.

I drive by here and walk on my way to and from work every day. When I first saw renovating activity I gasped and said to myself that I hoped the building was being re-purposed instead of demolished. I was so happy to see this building being restored and reused for such a good cause. Thank you for helping preserve such beautiful resilient structures!